Indian Classical Music by Rose Okada

Mala of Music by Rose Okada

Life with my Guru Khalifaji - Ustad Hafizullah Khan by his disciple, Rose Okada

My Father, Ustad Abdul Wahid Khan - The King of Music by La Monte Young and Rose Okada

The Great Saint and Composer of South India by Rose Okada

Indian Classical Music

by Rose Okada

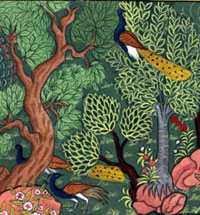

The ancient sages of India experienced and explored the deep relationships of sound, cosmology and the human psyche and body. Over thousands of years they developed a sophisticated and sublime music born out of these relationships, organizing it into an intricate organic living system or raga (melody) and tala (rhythm). The Classical Music of India, therefore, is based on the changing conditions of nature's daily and seasonal cycles and the related subtle variations in human feeling and sensations. Continually evolving for thousands of years, it has become one of the most beautiful music in the world. For some, studying this music is a way to refine their skills through learning traditional compositions and methods of improvisation; for others, it is a spiritual practice preserved and expressed in the language of music. Indian music is primarily individualistic. An Indian musician considers music as a medium to reach divinity and therefore they shut themselves in a room engaged in swara-sadhana (tone culture meditation) through singing or playing their instrument. The element of rasa, or the feeling expressed in the raga, is evoked through the artistry of composition and improvisation according to the particular musical ideas and phrases of a given raga.

"The six (6) major melodies (ragas) and the thirty six (36) minor melodies (raginis) with their beautiful bodies, emanating from the abode of Brahma, the transcendental being and sing hymns in honor of Brahma himself." — Pancham Sara Samhita, ancient text by Sri Narada

"Raga is living soul, raga means living souls (invoking a spiritual being) and raga has a "from morning to next morning cycle. Raga is always in between the notes and the breath is (like) a raga-moving. Every breath has a different feeling." — Faquir Pandit Pran Nath (1918 -1996)

"Our sages developed music from time immemorial for the mind to take shelter in that pure being which stands apart as one's true self. Real music is not for wealth, not for honors or not even for the joys of the mind – it is one kind of yoga, a path for realization and salvation to purify your mind and heart and give you longevity." — Ustad Ali Akbar Khan (b.1922)

Tal literally means clap and refers to the rhythmic cycles such as 7 or 16 beats in which pieces are performed. Each composition is based on a specific tala providing the rhythmic foundation for the melodic improvisation. Theka or rhythmic cycles are assigned specific basic bols (drum syllables) that are both recited and played on the instrument and distinguish it from another cycle. The interaction between the drummer and the melodic performer can be exciting as the percussionist imitates rhythmic patterns created by the melodic soloist, synchronizing on the sum (beat one) of each cycle.

"The laya is the pulse, the tempo. This is what you follow. You play in and out of it, you play around it. You take each beat and create patterns. The ideal way to play 16 beats (the rhythmic cycle tintal) might be in a combination of 4+4+4+4. But you can also do it in a 5+3+5+3 patterns. You can take a beat and extend it or shorten it." — Ustad Allah Rakha Khan (1919 - 2000)

"Rhythm is the essence of life. Without rhythm man cannot step forward." — Ustad Ahmed Jan Thirakwa (1892 - 1976)

India a vast country with the world's second largest population constituting a nation of many ethnicities, languages and faiths, boasts a music culture that is likewise multifarious. This great land was invaded from the north by Central Asian people several centuries before the British, who ruled India from 1757 -1947. The kingdoms of northern India came under the influence of the Islamic Persian culture, where several instruments such as the sarod, sitar, sarangi, and tabla were introduced during the 13th century. The influence of Islamic culture on north India was so strong that its effects could be observed in costumes, food, language and dance, as well as in music. It was during the Mughal Empire that two (2) styles of music evolved - Hindustani music from the north and Carnatic from the south representing the Hindu traditions prevalent in the south. Both Hindustani and Carnatic styles remain connected by tradition to the ancient Sanskrit texts that define the Indianness of the music.

The instruments and the musical styles of north and south differ. The sitar and tabla are not used in the south where the principal instruments are the plucked lute veena and the violin adopted from the west, along with the accompanying double headed drum mridangam and ghatam or clay pot. Both schools of music use the bamboo flute, although the south Indian flute is smaller. They both have a reed wind instrument - the shehnai in the north and the long nagaswaram in the south. The tambura (tamboura) or tanpura is a beautiful stringed instrument made from a gourd. It is used in both Hindustani and Carnatic music with a slight difference in shape. The tambura is used in all Indian music, radiating the SA or main pitch of the solo instrument or voice creating a meditative atmosphere. In Carnatic music, where a separate style for instrumental music does not exist, instrumental soloists perform melody from songs. In the Hindustani style, the instrumental music has developed out of the vocal styles. Regardless of the differences of the two styles, vocal music is the undisputed nucleus of both traditions. All the languages of the south, along with Sanskrit and even Hindi, are to be found within the lyrics of Carnatic music. In the Hindustani style artists also use Sanskrit, Hindi, Urdu and other languages. Vocalists themselves often sing texts in languages they cannot speak, for it is rather the music itself that is considered important.

Classical music in India has been undergoing phenomenal changes due to modern-day communications between the north and the south. Musicians from either style have been constantly adopting ragas and talas from their counterpart. The Hindustani sitarist, Pandit Ravi Shankar, for example, has been performing some compositions based on south Indian ragas, and many other northern musicians are also doing this as well as using rhythmic improvisational techniques form the south. Likewise, musicians from the south have been borrowing performing techniques, voice culture practices, rhythmic patterns and famous compositions from the Hindustani music system.

Both styles of Indian music have their roots in the Vedic hymns. Indian classical music is a spiritual discipline on the path to self-realization, following the traditional teaching that sound is God — Nada Brahma. By this process, ragas are the vehicle whereby an individual consciousness can be elevated to a realm of awareness where the revelation of the true meaning of the universe — its eternal and unchanging essence — can be joyfully experienced.

Mala of Music

by Rose Okada

I came to this earth to do music; to learn music, to play and share music and to teach music. While I was in the womb I listened to my Mother practicing the piano. She is a professional pianist and teacher and would practice for many hours a day. Because of that I know the piano repertoire very well and I find piano music to be quite soothing. Since my mother was so busy at the piano, my brothers and sisters and I all learned other instruments. Learning a musical instrument and taking private lessons including daily practice was a requirement at my house. My parents had seven kids, one for each note of the musical scale. I was the fourth note.

Indian Classical Music has its roots in the Vedas. The ancient chants use only three notes Sa Re and Ga. Even today the Brahmin priests chant using only these three notes. Sometime later the fourth middle note was added and then later the same three notes were added to make the full scale. S R G M + S R G M = S R G M P D N S.

In the history of western music, the same is also true. The ancient church music began with only three notes. The fourth note was later added making the tetra chord. Then two tetra chords were put together to form the musical scale. C D E F + C D E F = C D E F G A B C

The intervals (distance between two notes) of the two combined tetra chords are the same; whole step between C and D, whole step from D to E and a half step from E to F. Whole steps from G to A and A to B and a half step from B to C.

Sometime during the 18th Century western classical musicians decided to adopt the tempered tuning to the piano and to move away from music's natural state of the physics of music and just intonation. So the keyboard was adjusted to 12 exactly equally spaced notes per octave. This made all the notes of the natural overtone series out of tune except the octave! They did this in order for instruments to be able to play together in any key, but in doing this they only allowed for two scale types - major and minor scales. One of the best things that came out of this was the beautiful sound of the symphony orchestra. In the case of Indian classical music they retained the natural notes of the overtone series and have hundreds of different scales or ragas.

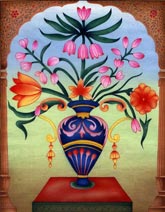

Pandit Pran Nath said that SA is Brahma and all the other notes were born from SA. Re is the water, Ga the earth, Ma is space, including the moon and other planets, Pa is the sun, Dha is the wind and Ni is fire. In just intonation and the physics of music, the perfect intervals are Sa Ma and Pa or the tonic, fourth and fifth notes of a scale. I believe that the musical notes are like beads of a mala. SA is one of the beads and you move to other notes and different octave of notes (other beads) and return to SA. Likewise life is also like this. Each person is a bead and we are born and move away from God in life but are still connected and eventually all return to God.

I can play seven instruments and have studied most of them for at least 10 years. I have had the best possible music teachers in every instrument, beginning with my very first Guruji, my Mother. On violin I studied with Dr. Shinichi Suzuki, who developed Talent Education, or the Suzuki Method. I took many guitar master classes with Manuel Lopez Ramos, who played in the Segovia style. After earning my degree in Classical Guitar performance I began to become dissatisfied with western classical music and its lack of creativity.

One day I heard a singer from India perform a raga concert. It was the most beautiful music I had ever heard! I soon began studies with her and also began playing the violin in that style. At the same time I began to play tambura for a friend who played sitar at a restaurant. The violin virtuoso, L. Subramaniam did a concert here and I was able to take a few violin lessons with him. I really loved Indian Classical music and in 1992 I took my first trip to India to study the music. In Mumbai, I studied Hindustani violin and on the second trip I found my true home, my Gharana, the Kirana Gharana. I began lessons with Pandit Pran Nath on vocal and Ustad Hafizullah Khan on sarangi. I soon became disciples of them both, giving me a double tie to Ustad Abdul Wahid Khan, who was Hafizullah's father and Pran Nath's Guru. During 1994 and 1995 I commuted to Seattle once a week with a small group of Portlanders to study tabla with the great Ustad Zakir Hussain.

Life with my Guru

Khalifaji - Ustad Hafizullah Khan

by his disciple, Rose Okada

In February of 1994, I was sitting on the floor of the "Concert room" at La Sagrita guest house in New Delhi India, waiting for the evening concert to begin. It was my second trip to India - the year before I had spent six weeks in Mumbai studying North Indian violin with D.K. Datar, but I really wanted to study sarangi. When I returned to Oregon, a friend introduced me to the vocal Darbari All India Radio recording of Ustad Abdul Wahid Khan Chisti Sabri. Even though he was probably 70 years old in the recording, his enormous vocal tone, perfect pitch, amazing improvisation and constant feeling of the SA was unbelievable. To listen to it made me feel a true oneness with God. Also after hearing Rik Masterson's beautiful sitar playing and vocal music, I was inspired to meet and study with his teacher and Abdul Wahid Khansahib's student, so here I was with Pandit Pran Nath and his vocal group. All of a sudden a holy man walked in wearing a beautiful white kurta. I immediately felt a very deep connection, and a great love for this man even though we had never met before and I had no idea who he was. A bansuri player performed first and then this holy man, Ustad Hafizullah Khan and his young son Samiullah Khan performed on the sarangis. It was so beautiful that it made me cry. I loved the music. I knew I had finally found my teacher!

I told the director, that I wanted to take lessons with Hafizullah Khansahib and he tried to discourage me and said "no, he's not that friendly - why not take lessons from such and such the esraj player?" But it didn't matter because I was already sure, so I began my lessons the next day at 3pm. At the second lesson Hafizullah Khansahib gave me his sarangi, a very special instrument which was his Guruji's sarangi to use and practice on. At home in Oregon I had a sarangi that I purchased a year before at a guitar shop in Michigan, but I wasn't able to tune it or figure out how to play, so I was thrilled to be able to learn from a great master. On top of that I was in such awe that this was actually Abdul Wahid Khansahib's son. I had daily lessons on the sarangi but was only in India for three weeks. I began with Raga Yaman, learning Guru Bina and a few tanas. Hafizullah Khansahib was quite strict and did not know any English at this time, but it didn't matter, he played and I followed.

After I returned to America we corresponded by writing letters to each other quite often. I had my letters translated into Hindi and I had to get his letters translated to English. The next two years I returned to Delhi for three weeks and took daily lessons on the sarangi with Khansahib. During this time I told Pandit Pran Nath that I would like to become Hafizullah Khansahib's disciple and Pran Nath Guruji said "Very Good!" So he arranged everything and many people from the vocal tour group joined us at Hafizullah Khalifaji's house for the ceremony which was on February 18th, 1996. All of Hafizullah Guruji's family was there, including his mother, Abdul Wahid Khansahib's wife. I had a short Multani lesson as part of the ceremony. Afterwards Pandit Pran Nath said "A very good feeling came from this ceremony, this is very lucky."

When I went to Europe with Pandit Pran Nath, he had me travel with his altar articles, including his initiation thread, placed in a small box wrapped in silk and malas given to him by his Guruji, Abdul Wahid Khansahib in my sarangi case, which was a great blessing. The concerts and classes in Bremen and Paris were wonderful, but I always was so sad to leave Hafizullah Khansahib and missed him terribly! In Paris, Pandit Pran Nath decided that I should accompany him on the sarangi while he sang Bhageshri. So thus began my sarangi vocal accompaniment career.

After Pran Nath Guruji passed, Hafizullah Khansahib invited me to stay at his home instead of the guest house, so during the next four years, I stayed in Delhi with Khansahib for one or two months. At this time I had two sarangi lessons a day, first thing in the morning and at 3pm in the afternoon. In the evenings Samiullah would have his vocal and sarangi lessons and I would accompany him on the sarangi and sometimes take singing lessons too. The food prepared by his daughters and wife was the best Indian food I'd ever tasted! I always gained weight! Hafizullahji was so kind to me!

We traveled together a few times and visited his house in Kirana and Abdul Wahid Khansahib's grave in Saharanpur. This was always a very high spiritual experience for me, and according to Hafizullah Khansahib he is my father too! He said that because we are tied in Guru-Shishya Parampara (The Master-Disciple tradition), my parents are his parents and his parents are my parents. In November 1996, my parents, Nancy and John Smith, who are from Michigan, went on a world tour which included Delhi. Hafizullah Guruji, Samiullah and Iqbal Mohammed (a family friend who spoke English) met my parents at their hotel and brought them back to Khansahib's home for dinner and breakfast the next day. So they were able to meet my Guruji and his family! They also visited him in Oregon in July of 2001 and Hafizullah Khansahib called them Mom and Dad.

Every lesson I had on both sarangi and vocal from Hafizullah Guruji was like a full concert - alap, vilambit, sargam, drut and tanas. He composed many beautiful melodies in various ragas and liked to combine ragas in his own playing. He also composed his own ragas, such as the beautiful Sohini Gori. Ustad Hafizullah Khan always performed in the very slow vilambit jhoomra with 56 quarter beats, with a step by step unfolding of the notes of the raga. I love this part of his meditative playing very much.

Hafizullah Khansahib came to USA three times during 2000 - 2002, for very successful sarangi concerts, vocal and sarangi classes and lessons in Portland Oregon, Seattle, San Francisco and New York. Soon after he arrived the first year he was talking to Samiullah in India on the phone who asked "How do you like America?" "Fantastic!" answered Hafizullah Khansahib. He really enjoyed being here. He felt life in America was very easy compared to India. "In India" he said "you have to wash your clothes daily, there is so much dirt and dust, in America once a month, no problem!" I made Hafizullah Khansahib's breakfast every day but he always insisted on ironing his own kurtas for the concerts and sometimes even cooked dinner. He was not very demanding and was a simple person with a lot of love and music to give. Hafizullah Guruji was my best friend, my father, my brother, my teacher and Guru. We were very close. While in Portland, he wanted to go everywhere with me - shopping, gigs, Japanese tea ceremonies, and visiting. He enjoyed listening to my Suzuki violin and guitar students and especially loved the small children playing on tiny violins.

At almost every concert, Hafizullah Guruji would have me perform a "duet" with him. He was really taking the best care of me and always gave me chances to perform. He was just like a mother bird that would gently, little by little push the baby bird out of the nest. At first he would do the alap and have me follow him, then each year he would give me more and more to play on my own.

Hafizullah Khansahib would tell me that the Guru-Disciple relationship was very special and how amazing it was that we met from opposite sides of the earth. He believed that our association was a true gift from God. My own feeling from being a disciple of both Pandit Pran Nath and Hafizullah Khansahib is that it is truly a transcendental & magical relationship. The love and care are so strong in these relationships that I still feel it! Even the teaching continues!

One of Khansahib's goals was to perform for Pandit Pran Nath's Urs and so his New York debut was on June 13th, 2002 at the Mela Dream House. He arrived in America on his birthday and left for India July 13th. Hafizullah Khansahib passed from this earth on August 13th at 12:45am in a hospital in New Delhi surrounded by his family. According to Samiullah, before he died he said "tell everyone I love them and send them kisses." At his request, Ustad Hafizullah Khan was buried in Roorkee, at the Sufi shrine of Khalir Sharif.

On Thursday August 15th, 2002 India Independence Day, I had a celebration of the life of my Guruji Ustad Hafizullah Khan at my home. It was a happy occasion and many friends and students came. I shared stories, photos and music of Hafizullah Khansahib. After his death I felt a lot of love, so I was not sad, in fact I feel so grateful to have studied with him for the 8 years and also that I had just spent time with such a great musician. He performed 11 beautiful concerts in America and had me play sarangi with him at every concert. He was a very fun, generous and loving Guruji.

Two days after Hafizullah Khansahib's death, I was alone in my room and awoken at 2:45am by the loud sounds of my sarangi. All three gut strings and many of the sympathetic wires were twanging and lost some of their tension. I immediately sat up and said "Yes Guruji, I will practice every day!" It was as if he came to me to say goodbye. In India the time would have been 3:15 in the afternoon - after the tuning of the 35 resonator strings - the exact time of my usual afternoon lesson!

In February 2003, a few days before the anniversary of my initiation with Hafizullah Khansahib, I was performing the Maru Bihag that he had taught me on sarangi with Alfred Lisanti accompanying on tabla and I looked over at the tabla hat on the floor and I saw that a perfect OM symbol had appeared in the tabla powder. The magic of the Guru-Disciple relationship continues!

At the August 9, 2003 memorial concert for Hafizullah Khalifaji at the Mela Foundation in New York sung by La Monte Young and Marian Zazeela, another touch of Guru-Shisha magic happened. They informed me that a mysterious mistake appeared in the program notes - my name ran right into his name with no spaces, indicating to them that Hafizullah Guruji wanted to be very close to me and that he was reaching out to me in every way possible!

Currently I am finishing a book on the sarangi, including a method book of Hafizullah Khansahib's compositions and teachings. Ustad Hafizullah Khan Khalifaji is forever at my side. I will always perform on sarangi in his name.

My Father, Ustad Abdul Wahid Khan - The King of Music

by La Monte Young and Rose Okada

During his lifetime, Sufi Abdul Wahid Khan Chisti Sabri was the acknowledged master of the Kirana style. His revival of Khayal at the turn of the 19th century stands, in itself, as a virtually unparalleled contribution to the recent history of Indian Classical music.

Abdul Wahid Khan began his studies at an early age with his father, Abdul Majid Khan, learning vocal and sarangi. Around age 12 he was sent to Kolhapur to study with Haider Baksh Khan, who was a disciple of the reknowned master of the beenkar (vina) and voice, Mian Bande Ali Khan.

Although a youthful prodigy of the Kolhapur court, remaining unchallenged after his public debut there at age 18, Abdul Wahid Khan had no inclination to spend time singing in the courts. Instead he lived a devout, reclusive life, singing in the presence of holy men and at the tombs of Sufi saints and only occasionally sang in public.

The most striking fact on his performance was apparently his alap. The time he took, the care, to elaborate the raga was exceptional among khayal singers: he might take hours on one raga.

When Salamat Ali Khan was asked by one of his disciples for a description of Abdul Wahid Khan, he replied, "He would begin to improvise in Lahore and you could travel to Delhi and back, and he would still be improvising. More than that you don't ask."

Ustad Ali Akbar Khan said that when most musicians came to the radio station, they sang their raga and went home. When Abdul Wahid Khan would come, however, he would sing his scheduled broadcast and then just continue for 20 hours or so. People would come and go, and he would still be singing.

His command of the art was such that no other musician ever performed in his presence. Abdul Wahid Khan practiced Todi and Darbari day in and day out. When asked why he limited himself to only two ragas, his response was that he would have dropped the second one also if morning time could last forever. One lifetime, according to him, was not enough to do justice to any raga. He was forced to change from Todi to something else only because of the setting sun and the gathering darkness.

Born in Kirana, he later moved to Lahore where he made an independent career until his death in Saharanpur in 1949. Ustad Abdul Wahid Khan was inferred the title of 'Sirtaaj-e-Mousiki' the Crown of All Musicians, The King of Music.

He had a most religious and pious attitude to life, paying homage throughout his life to his pir the Sufi, Khwaja Ali Ahmed Nafi Alam, a saint living in Multan in the Punjab, now Pakistan.

Requiring rigorous discipline and fierce devotion, Abdul Wahid Khan accepted very few disciples, among them Pandit Pran Nath became one of the most important through his ceaseless practice, natural talent and extraordinary ability to serve his master. For almost 20 years he served his Guru and in 1970 came to the USA where he has many disciples in New York, California and Oregon including the American composers La Monte Young and Terry Riley.

Ustad Abdul Wahid Khan had only one surviving son, who followed in his father's footsteps to also become a great musician on the sarangi and voice, Ustad Hafizullah Khan. Khalifa Hafizullah Khan was a staff senior artist with the highest ratings at All India Radio in Delhi for over 30 years. I became the disciple of Khalifa Hafizullah Khan in 1995 and studied sarangi and vocal with him for eight years. He told me that since we were Guru and Shishya that my father and mother are also his and his father and mother are also mine! So that makes the great Kirana singer Ustad Abdul Wahid Khan my father too!

The Great Saint and Composer of South India

by Rose Okada

Sri Tyagaraja is one of the great illuminaries, a minstrel of God, who came to this earth to contribute to man's spiritual and earthly happiness. His songs tell of the eternal wisdom of the sages of India and he is the rare example of a person knowledgable in sangita, sahitya and bhakti. He has inspired so many musicians and composers who came after him. His melodies are so fragrant and beautiful, that most of his compositions are the permanent and standard repertoire of every performer of classical music. Many of his pieces are noted for their poetic imagery, bright ideas and delicate sentiments. He was a daring experimenter with a gift for shaping new ragas.

Tyagaraja lived in a time of intense musical activity in fact it was the brightest period in the history of South Indian music. During this golden age, the famous Carnatic trinity of musicians and composers included, Tyagaraga (1767 - 1847), Muthuswami Dikshitar (1776 - 1827) and Syama Sastri (1762 - 1827). Their profound musicianship, creativity and deep spirituality were invaluable. Tyagaraja was a born genius, a gifted composer and a brilliant singer and veena player. The fact that he expounded Devagandhari raga for six days during his stay in Chennai is proof of his extraordinary creative talent. He emphasized in no uncertain terms that it was possible for a person to attain Moksha through the path of pure music. God himself was Nada Brahma - the embodiment of music, and the contemplation of God through pure music led one to the Divine consciousness longed for by sages.

Born in Tiruvayyar in Tanjore District, on 4th of May 1767, Tyagaraja was a Telugu Brahmin. The discovery of the horoscope of Tyagaraja carefully preserved on a palm leaf in the Walajapet Collection has helped to establish this date. He was named Tyagaraja after the deity of Tivuvayyar and in his compositions used the name mudra. As a boy he studied with Sonti Venkataramanayya, who soon discovered his musical genius. He also studied Telugu and Sanskrit with his father and attained scholarship in these two languages. At age 18, Haridas from Kanchipuram came to him and asked him to recite Rama nama 96 crores of times. Tyagaraja took it as a command from above and completed the task in 21 years. He recited on an average 1,25000 namas every day with his wife joining him. By the middle period of his life, his name and fame as a composer of front rank had spread far and wide.

Tyagaraja was an inspired composer and it is quite interesting to know how his disciples recorded in notation the songs that flowed out of his mouth. They wrote upon mango planks with steatite pencils. The planks were 18 inches long and 9 inches wide and a half-inch in thickness. They were coated with black leaves of the plant, bryonia grandis. One disciple concentrated on the Pallavi and recorded the notation and went to the nearby riverbank to memorize it. The second disciple directed his attention to the Anu Pallavi and likewise left for another place to memorize it. The third wrote the Charana and the fourth sishya wrote the sahitya, after understanding the words. When another song came, another set of four disciples for ready for the purpose. The next day the disciples sat together, consolidated their notes, learnt full pieces and submitted them to the master.

Tyagaraja perfected the highly evolved musical form called the Kriti. That Tyagaraja had digested the famous work Svararnava (obtained providentially) is proved by the charana of the kriti, "Svararagasudharasa" in Sankarabharana raga. This work which the sage Narada is said to have presented him, contains the interesting s'loka:

Atma madhya gata; Prana: Prana madhya gato dhvani:

Dhvani madhya gato nada: nada madhye Sadasiva

In the center of the body is the Prana (breath or life force): in the center of the Prana is the dhvani (sound); in the center of the dhvani is the nada (musical sound); and in the center of the nada is Sadasiva (the supreme Lord.)

Tyagaraja has composed in all the 72 Mela Cartas and we owe the knowledge of many rare ragas to him. Half of his compositions are about the Ramayana and he also wrote Bhajanas. Whenever he visited shrines during his pilgrimages he composed songs (usually 5) in praise of the local deity. He has embodied in his compositions, all the truths of the Upanishads and sacred lore. As the father of modern Geya Natakam or opera, his genius is observed in the dramatic instinct, literary and poetic skill, great powers of imagination and his beautiful melodies. Tyagaraga has also written group kritis with the most famous being the Pancharatnam or five gems. His talent for writing varied colorful melodies interwoven with sparkling rhythmical designs is clearly seen in these pieces. There is also a set of 100 devotional songs composed in 100 different ragas offered as a garland to Hari.

Pioneer artists like Tyagaraja set up musical standards for all times. He had the largest number of disciples know to have been associated with any composer in India's musical history. These disciples and their disciples became distinguished composers and musicians and Tyagaraja's radiant personality beaming with spiritual greatness left an indelible impression on their minds. Tyagaraja paired off his disciples according to their pitch and capacity of voices and taught to each pair not more than 200 kritis. Thus he distributed his thousands of compositions among the several pairs of disciples. In those days, the art of printing had not yet come to South India so the songs had to be frequently repeated.

Tyagaraja passed away on the Pushya Bahula Panchami Day of the Parabhava samvastsara, corresponding to the 6th of January 1847. Ten days before his death, he had a dream that he would be called to the lotus feet of the Lord. On the day before the event he said "Tomorrow at 11am, Sri Rama has promised to take me back; please perform bhajana continuously from now onwards." This news soon spread and a large number of people gathered the following morning to witness the closing moments of this Great Saint. Tyagaraja sat in yoga samadhi. At the predicted moment, the congregation heard a mysterious nadam (sound) emanating from the Saints' head. Soon they saw a bright halo of light flying off from his head and vanishing slowly into the atmosphere and proceeding in a northerly direction. The mortal remains were then taken to the Kaveri bank with all the honors, accompanied by music and placed next to his Guru.

Every year, in January around the day that Tyagaraja died, the Tyagaraja Aradhana festival is held in Tiruvayyar. Attended by thousands, the festival draws top-ranking artists. We go to a Tyagaraja festival, to listen to this source of divine joy, inspiration and comfort. Every variety of human experience is presented in his songs. Tyagaraja's compositions have invested Carnatic music with a perpetual vitality. Tyagaraja has become one of the world's immortals.

Bibliography

Great Composers Book Two, Tyagaraja by P. Sambamoorthy, head of department of Indian Music, University of Madras, The Indian Music Publishing House Madras 1954

Euphony, Indian Classical Music by L. Subramaniam and Viji Subramaniam

East West Books (Madras) Chennai, Bangalore, Hyderbad 1995

All articles © by Rose Okada, 2005, 2006, 2009. All Rights reserved.